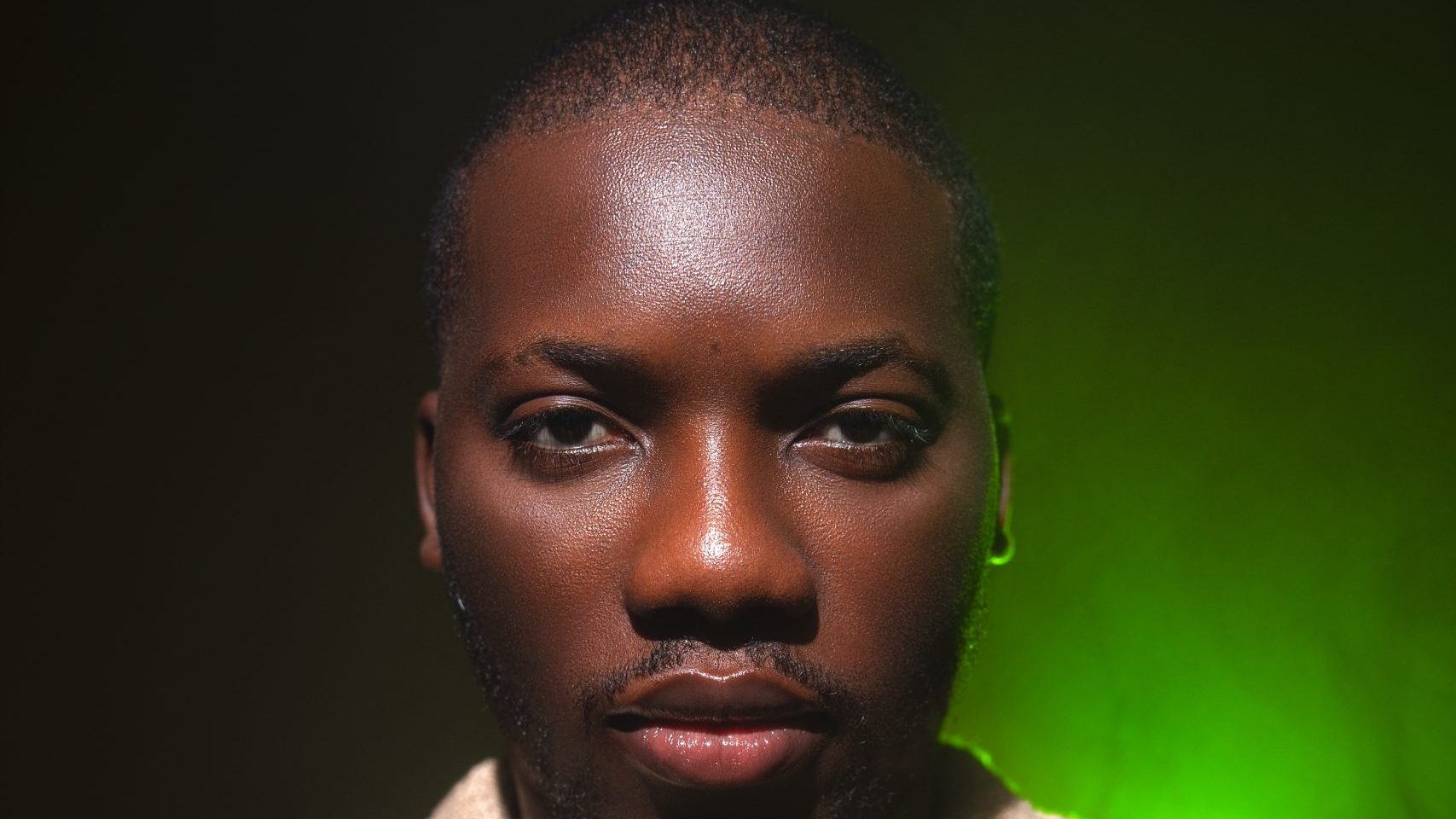

Moyosola Olowokure, also known as The Sun-Kissed Poet, creates work that refuses to choose between the sacred and the human. Her debut EP “Dirt and Divinity” exists in the tension between holiness and frailty—a space most believers inhabit but few artists dare to name. With her breakout piece “Sex Is a Kind of Death” crossing 20,000 streams, Moyo has established herself as a voice unafraid to draw connections between worship and intimacy, grief and grace, doubt and devotion. Working between Lagos and Abuja, she writes poetry that bleeds across boundaries: love poems become prayers, spiritual reflections turn into confessions of desire. In this conversation, Moyo opens up about processing her father’s passing through art, navigating religious spaces with radical honesty, and why she believes the in-between space, where we’re all still learning, might be the most truthful place of all.

What’s the one thing that you would want everybody who encounters you and your work to know about you?

I think something I want everyone to know is that I am deeply flawed but also deeply aware of God.

You call yourself the sun-kissed poet because to you the sun symbolises both God and your late father. As you release this new project, “Dirt and Divinity,” about divine inheritance and human frailty, how do you think your father’s presence lives on in your work, in this particular work?

I like this question. I think that much of the EP is me working through grief. And so, the fact that there even is grief to work through is evidence of my love for him and his impact on me and our entire family. I think just the simple fact that there are poems to be written about what it’s like losing him or how that has coloured my subsequent relationships, I feel that does honour him in some way.

“Dirt & Divinity” is such a visceral title. Walk us through the moment you realised this was the phrase that captured what you needed to say. Was there a specific experience or scripture that crystallised it for you?

I think the first piece that was written for this collection was just “Dirt & Divinity” itself. The piece that’s the title track, the very first track, it’s about some sort of addiction and how it can leave you viewing yourself as dirt. So there’s a lot of imagery there about mud and dirt and filth and all of that. And then at the very tail end of the piece, there’s just this growing awareness of “but there is God, a God who has his gaze on me”. In writing that particular poem, “Dirt and Divinity” just came out so strongly, and it was just the perfect title for that piece. Then shortly after, I realised that I do want to do a collection, a wider exploration of this concept of frailty meeting perfection and what that looks like in various areas of my life and this life in general.

You described the project as “existing where holiness touches frailty”, as the tension that many believers live in but are rarely able to articulate. So why was it important to you to create art that sits in that middle space, instead of trying to resolve it?

I love this question so much. Because I don’t think that life is ever really resolved as long as it’s still being lived. There are always questions. There are always doubts. There are always hopes and dreams. At least for me in the headspace I’m in right now, what really rings true about the human experience is that it is a balancing of two seemingly opposing truths; it is an in-between space. As much as for our ease and our comfort or maybe even our sanity, we try to oversimplify things and say things are either bad or good or black or white or dirt or divinity. But a lot of times it’s both, if not every time it’s both. And whatever underlying discomfort we’re running away from by trying not to acknowledge these two truths, the moment we are able to look it in the face and just stick with it, it might make us more at peace with ourselves and with each other.

I see where you’re coming from with that. Let’s talk about “Sex Is a Kind of Death,” which was your debut, which has now crossed about 20,000 streams. So you described that as exploring the similarities between sex and worship. That’s very bold from a religious angle. So what made you brave enough to say that?

What made me brave enough to say it was the fact that it had already been said. I was reading through Isaiah and the prophets in general, and how when they’re giving their charge to the people of Israel or when they’re telling them about what they’re doing wrong and how God wants them to come back to him, there’s a lot of imagery about husband and wife, prostitution. You just see in the Bible a lot of the time, especially in the Old Testament, you see idolatry being juxtaposed quite often with adultery. And so it makes you, or it made me wonder, what is it about this romantic act or this act of intimacy that God has designed in such a way that even He Himself, when he puts His words in the mouth of prophets, he compares it to our relationship with Him.

I find that a lot of times, you may hear a gospel song or a worship song and think it’s a love song or a romance song. A lot of times, you hear a love song and think it’s a gospel song. And yeah, I don’t even think it’s often one or the other because the feelings you have toward God and the feelings you have towards someone that you are intimate with exclusively, there’s just a kind of power, and there’s just something about it. “Sex Is a Kind of Death” is definitely an exploration of that, what that means to relate with God in the kind of reckless devotion and intimacy as you would with a lover. Even more so.

You’ve said that piece captures “the soft single panic before a mind-blowing profound truth, an orgasm of the soul.” That phrasing itself is poetry. How do you navigate creating work that is honest about pleasure and about spirituality?

My only honest answer to that is that I have to. Because if I don’t write about what is true to me and what I feel and what I see, I might run mad because I ponder a lot. And “outlet” doesn’t quite capture it, but for lack of a better word, poetry is an outlet for that. The more truth we are able to accommodate personally and as a society, the more sane we will all be. I just have to. If I don’t write about it, then what am I really doing with my art if I’m not being honest with it, if I’m not telling the truth with it?

Valid. On the closing track “We Will Not Stop,” you described it as an anthem for all believers living in the gap, standing on grace as the bridge. So who are you singing to in that moment? Who do you think needs to hear it?

A conventional answer may be “everyone”, to be very honest. But I would just say specifically people that may have at one point or the other questioned or doubted their ability to love God and to just love in general and to love light and to spread light in the world and to be an agent of change, whatever it is that maybe your inner child hopes to do in this world and hopes to connect with, whether it’s God, whether it’s love, God is love. That person who needs the reminder that they are still capable of love and they are capable of committing to love and committing to God, no matter how low they feel they’ve gone.

Would you call yourself a gospel artist?

No. I don’t think I would. I might call myself a Christian artist. Yeah. But I feel that’s more a function of the fact that I’m a Christian and an artist.

Okay. So you are a Christian who makes art that doesn’t shy away from addiction, from desire, from doubt. So, have you faced any pushback from your religious community, and how do you balance your faith with artistic honesty?

Luckily enough, I would say no. I actually have not. At least not that I’m aware of. I mean, I know that for “Let’s Be Light”, some people had some issues with the line, “an artist is like God” or “a poet is like the Holy Spirit.” One person literally quoted “this is blasphemy”, and that actually felt pretty encouraging to me because it just felt, oh, I’m actually striking a nerve. I’ve never been out to make art that is palatable or easy or surface-level. My words heal, they soothe, but I would not say they are by any means easy if that makes sense. And so that pushback in as much as that is just not in the religious community or people that are close to me in a religious or spiritual setting.

As for balancing, I don’t even think I’m balancing. I feel they both feed into just being an artist and being religious or being spiritual in any way. I can’t really be an artist without being spiritual. I don’t think I can fully be spiritual without being an artist. So those two things work hand in hand. Yeah.

Okay. So speaking of “Let’s Be Light,” in it you say “, there are lessons of faith and love I must teach even as I am still learning.” What made you decide to lead from the place of still learning rather than waiting until you had it figured out?

Oh, this is so important because I don’t think there is a place where you have it all figured out. I feel that place is a myth. I feel that place doesn’t exist. At least not on this side of eternity. And we really live in a world that is so outcome-hungry and so finish line-hungry that we almost detest process. And AI really, the lesson in that has amplified that way of living where it’s okay, what’s the end result, what’s the finish line, what’s the finished product. And when we treat ourselves as humans that way, we really rob ourselves of a lot of humility, a lot of awe that we may have for the process of becoming. And so, yeah, that’s what the line is, just honouring the truth that we are all in between. No matter how high up you are or how low down you are, you are still in between something and something else. And so, you are always teaching, but you are always still learning.

Okay. So there are biblical narratives woven throughout the project. Is there a particular scripture or a Bible story that kept coming back to you while you were creating “Dirt and Divinity”? Is there one that felt like the backbone of everything?

No, I wouldn’t say that there was a backbone. Each piece really had its own spark moment. I’m just reading my Bible or listening to a praise song and inspiration for a specific piece and they all blended together in that they all had the same “Dirt and Divinity” theme, but no, I wouldn’t say there was any particular scripture that anchored it all.

Okay, thanks. So you worked with a producer called Joshua ‘IJAK’ Akunnakwe on this. Why exactly did you choose him? What is it about his sound that made you trust him with work this personal? And how did you two find a sonic language that would narrate these themes?

What made me work with him was that he cares. He actually cares. So he’s not “Oh, let me wrap it up and get it done and take your work and be going.” He’s “What are you trying to say here?” All the questions you’re asking me, Jackie asked, and he tried to incorporate them into the sound. So he’s very conscious. He cares. So that’s why I worked with him.

And in terms of translating things, I would say he’s very creative in the sense that he can find unconventional ways to symbolise things. So, for example, on “Sex Is a Kind of Death,” the initial whispers that were there were his idea, and I felt it just really started off the piece so beautifully. Even for “Imago,” there are a lot of structural arrangements that were his idea. And so, you can just tell that this person really cares about the work that he’s doing. He’s so committed to growing, and he’s so committed to that in-between space. He’s so comfortable in that in-between space of “oh, I’ve come a long way, but I still have a long way to go.” And it just translates into everything that he makes and that we make together. So yeah.

We can see that grief, spirituality, and romance are your core themes. So when you sit down to write, do you already know which one you’re working on in the moment, or do they all bleed together? Have you ever started a love poem that surprised you by becoming a prayer or something?

Oh yes, all the time. “Sword”, I don’t even know, it started as a mix of so many things. It started as a mix of grief, a mix of romance and a mix of spirituality and faith because there are themes of loss there, there’s romance there, there’s worship and all of that there. They really do bleed into each other. Many times, I would start off trying to write a piece, and I’d end up writing two pieces at once. So, I might not even know. I might carry on writing and then read through the poem and then realise that oh wait, this is actually two different poems talking about two different things. But the two actually came as one or they came to me as one even though they were different. And so yeah, a lot of times they do blend into each other.

You started writing poetry in primary school with birthday poems for loved ones and romance poetry for your crushes. So, do any of those crushes know? Do they know that they were your early muses? And most importantly, were the poems actually good?

Yes. Oh my goodness. I’ve always worn my heart on my sleeve, whether I like it or not. Even before I actively identified myself as a poet, I just loved sharing my work. If I write a poem about you, you’re going to know. And I mean, I had very painful moments where I would share my poem with somebody, a crush. In fact, I won’t say his name. But his name starts with M. I shared my poem with him, and he laughed at me in front of the whole class, which was really formative. I can’t have stage fright anymore. Once you do that, you can get through anything. Would I say the poems were good? Definitely. I love them. I would still be proud of them tomorrow, even though I’ve not seen them. I don’t have them, but yeah.

That’s great. So you moonlight between Lagos and Abuja. Which gets the love poems and which one gets the grief? Or does each city pull different things out of you creatively?

Oh my goodness. This is so funny because I was just talking about this. Abuja is a lot softer. And so yes, I would say Abuja brings a lot of the tender lovey-dovey stuff from me. Definitely Abuja. I would say Lagos brings me face-to-face with my deepest fears and my most hurtful losses. And so yeah, definitely they bring out different things. I’d say Abuja is a bit softer and so the poems are softer.

So if someone discovers you for the first time through “Dirt and Divinity” and they are standing in that same tension between their faith and their humanity, what’s the one thing that you hope they hear you saying to them?

I hope they hear me saying that God knows everything that they are. He sees everything that they are and he loves everything that they are. And all that they will be or think they should be or hope to be is already inside them 100%.

The album dropped on November 28th. So, what did that day look like for you? Were you celebrating loudly? Were you sitting quietly with it? Were you somewhere in between? And what were you praying for as the work went out into the world?

I was asleep. I was asleep when it came out. Maybe I’ll just talk about the day after. I don’t really do so well with listening to my own work. Other artists, some other artists can really jam their own work, but for me, I was forced to listen to it for the first time when preparing for this interview, actually, I’ll confess. And that day, I was just happy. I just felt relieved, to be honest. I just felt happy that it was out, and I just felt grateful that people were already connecting to it. A lot of the pieces were pieces that people already sort of knew. So yeah, that was it.